The wonders:

The Substack part of my digital space has been quiet. One of my New Year’s resolutions last year was “depth instead of breadth,” while I was trying to organize my commitments. But I’d much rather grow into more activities than feels comfortable at first than stifle the things I love doing. So hi, I hope to be less quiet this year. Lately, I’ve been reflecting on Americans’ expectations of each other and our relationships, beliefs, and reactions to surprises perking up along our collective journey, especially through the pandemic. How do we choose to love and stand by a country when we don’t always agree with what goes on within it?

When I was six years old, I looked up ebulliently four feet above, pledging my allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, before I fully grasped the essence of this promise. Knowing what I know now, I know that I pledged to stay loyal and faithful to the United States as it sent troops to a war in Iraq, faced two crippling economic recessions, and pulled back from progress in climate change. I also stood by the country as it elected its first Black president, made gay marriage legal, and elected its first South Asian American Vice President. Through each wave of change, I pledged to unequivocally stand by the country, even if the meaning of its intentions became muddled. I wonder if children, after watching years of civil unrest, slapdash fixes to disruptions in education, and haphazard dealings with the health care system, feel just as comfortable standing in a classroom with their hand pressed over their hearts, conferring allegiance to our flag, especially after sheltering at home during this wave of the pandemic.

My parents became citizens of the United States one day in the spring of 2006, after they walked into a blue and airy room in a Maryland courthouse, took their Oath of citizenship, and gained a new title by the power vested in the court officials. When we visited India a summer later, our family curiously traced their fingers over our new passports, rapt with the golden letters which spelled United States of America below an eagle. Patriotism was not hard when it was triggered by such veneration.

In college, friends from other countries asked about the ubiquitous presence of the American flag, hanging high in dorm rooms, garages in suburbs, outside of McDonald’s. The American flag has become such a staple of American life, that its presence becomes muted in the background. I can only remember it now in very particular moments: hanging half-mast after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, draped behind presidents during their election speeches, and in the classrooms of my childhood.

Patriotism has a legion of meanings to a multitude of people. According to a 2014 report by Pew Research Center:

“Overall, 81% of Business Conservatives and 72% of Steadfast Conservatives say the phrase “often feel proud to be American” describes them well…And just 40% of Solid Liberals say they often feel pride in being American; 60% say that characterization does not fit them well.

In addition to high levels of patriotism, the groups on the right also are most likely to say they have a sense of honor and duty. About seven-in-ten Business Conservatives (70%) and Steadfast Conservatives (68%) say the phrase ‘honor and duty are my core values’ fits them. Far fewer in the other typology groups, including just 40% of Solid Liberals, say this description applies well to them.

A large majority of Americans (74%) say the phrase ‘compassion and helping others are my core values’ describes them well. This description is embraced by majorities across all typology groups, though Solid Liberals (82%) are the most likely to say it applies to them.”

In the modern day, patriotism is often equated to American exceptionalism, respecting the flag, and participating wholeheartedly in national celebrations with unabashed pride. But as Benjamin I. Page, coauthor of Democracy in America? What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It notes, “To most, patriotism means inclusive love of family, friends, community, and country – in all their diversity and messiness – without hatred of the ‘other.’ To most, patriotism allows for criticism, seeks progress, and embraces cooperation rather than conflict with the wider world.”

Rachel Blum, another political science author, states that patriotism can be a characteristic or an action. Patriotism can be “an active state of caring for the country you call home and the people in it. Caring for your country is different from blindly loving it, or swearing fealty to its leaders. It bears more resemblance to the way members of a family care for one another: paying attention, taking responsibility for one another’s well-being, having difficult conversations about problematic behaviors, and protecting one another from abuse.”

Patriotism does not have to mean celebration and pride; it can also mean doing the good and necessary work, creating waves of change through persistent efforts. Loving, even towards a country, is active rather than passive, and similar to love towards any other action such as knitting, cooking, writing, or dancing: it needs to be learned and practiced. People know how to love a new partner, a new job, a new trade whose rejections and failures one has not yet faced. But to love something over time after trials and tribulations is great work — it requires patience, devotion, dedication, and a loss of one’s own self to something greater. To love America is to be willing to sacrifice one’s own quest for power, recognition, and comfort, and to dedicate oneself to the gritty work that has no glamor. This ideal is exemplified in Georgia, whose grassroots organizations have sacrificed as such to do the quiet work that has benefitted the country in historic elections. And to do this work, love cannot exist without acceptance and honesty.

“I criticize America because I love her,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said in a speech about the Vietnam War, “and because I want to see her to stand as the moral example of the world.” Whether or not we believe “we often feel pride to be an American” or that “honor and duty are my core values,” most of us believe that “compassion and helping others are my core values.” What greater ideal can a country strive for, than to have all of its citizens consistently working to have compassion and help others? Just these small but consistent acts of service can uphold a country to better standards, help it evolve in an upwards trajectory, and strive to make it a more perfect union. While I no longer stand in a classroom to recite the pledge of allegiance, I reflect on its implications. It’s not, after all, a passive acceptance of complacency but can be a call to action.

Things I’m keeping an eye on (and you can too!):

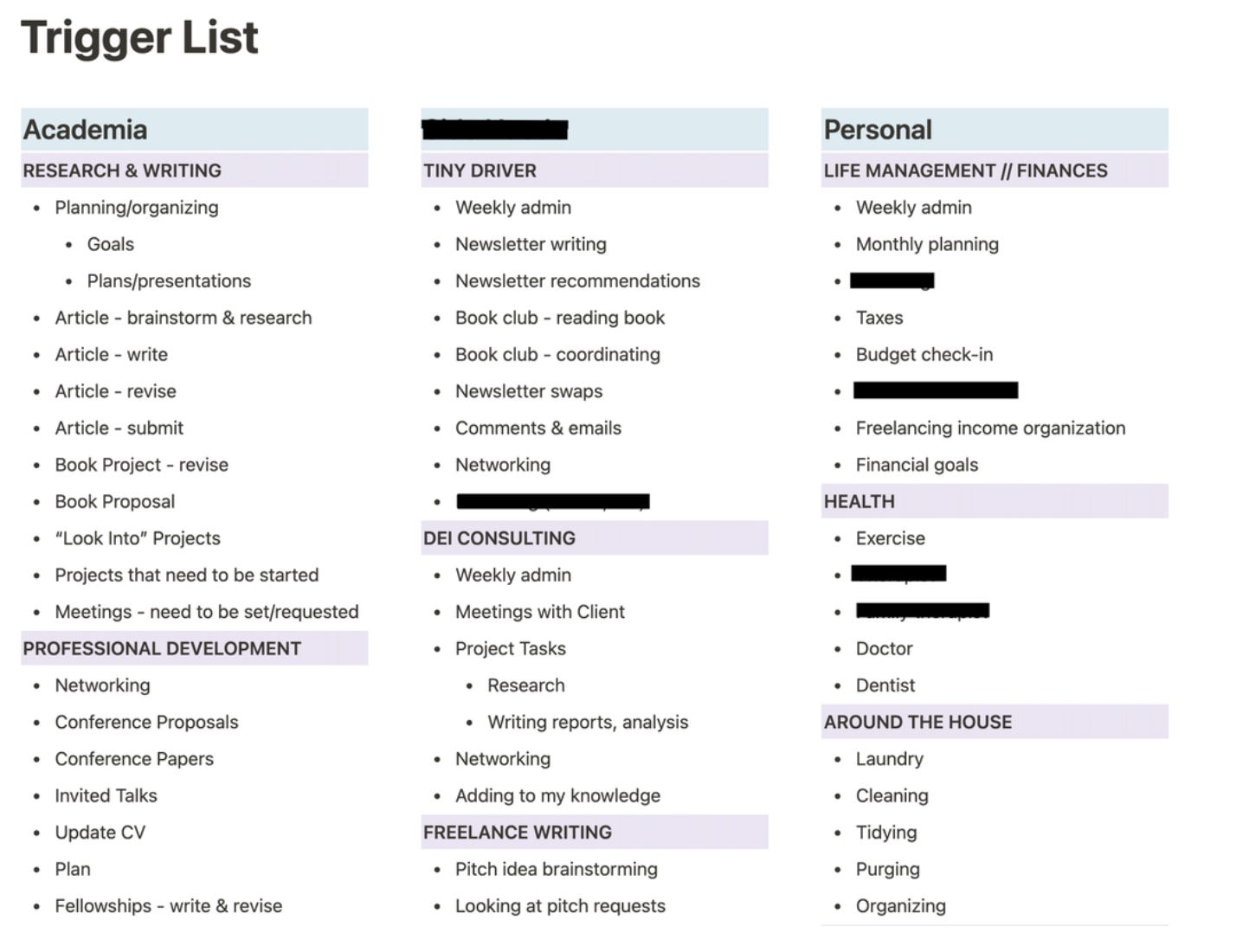

One of my favorite newsletter writers Ida Yalzadeh has given an inspirational layout of the app Notion, which is helping me sort through all of the nodes of my brain:

She has so much great content on process, writing, research, and pedagogy - please peruse her reading!

This Twitter thread gave me a smile. It’s a living example of what actionable compassion can do.

Community Center:

If there’s anything you’re reading, writing, feeling, eating, organizing, please share. For any other comments, feel free to reach out via Twitter, Instagram, or email. Can’t wait to listen. Sending lots of love.